150 years ago, The Times said Liverpool was the most drunken town in England. How are we doing now?

Beer and loathing in Concert Square

Concert Square, Friday night. You know the drill. Shisha smoke, pockets of fancy dress. Two trays of shots weaving through a baying crowd on each of a waitress’s palms, like some circus act sambuca sommelier. A suspicious number of men wanting a cubicle when there are clearly unoccupied urinals (see also: cash point queues). Me, recounting a story for a bloke called Ben, a couple of years younger than me. It’s this.

A few nights earlier and just round the corner, while wandering down Bold Street in search of a souvlaki, a strange scene unfurled in front of me. It was around midnight and a man had taken unkindly to being ejected from Coyote Ugly. The bouncer tasked with removing him (and the six or seven-strong pack he was with) got a nasty shock when the man pivoted, seized a plastic chair that was sitting outside and tossed it at the Coyote window.

Angry, the bouncer gave chase to apprehend the chair-slinging assailant, who — needing a tool of defence — grabbed another chair and headed south down the street with the rest of his group, all hot-stepping backwards like a retreating infantry in high heels and Armani trainers. Eventually, the bouncer gave up the chase and they made off, the main culprit slurring expletives with a plastic chair under his arm. Half the street, by this stage, was filming.

Ben laughs a lot. Then he tells me things like this are why he chose to come to uni in Liverpool and drains his pint.

It’s an observation you’ll hear quite a lot. That scenes of mad drunken bacchanalia are, if not unique to here, then at least something Liverpool does best. Anecdotally, Liverpool feels binge-y. And statistically it has been particularly so in the past. In 2007 the now-defunct Daily Post called the city England’s “capital of the binge culture”.

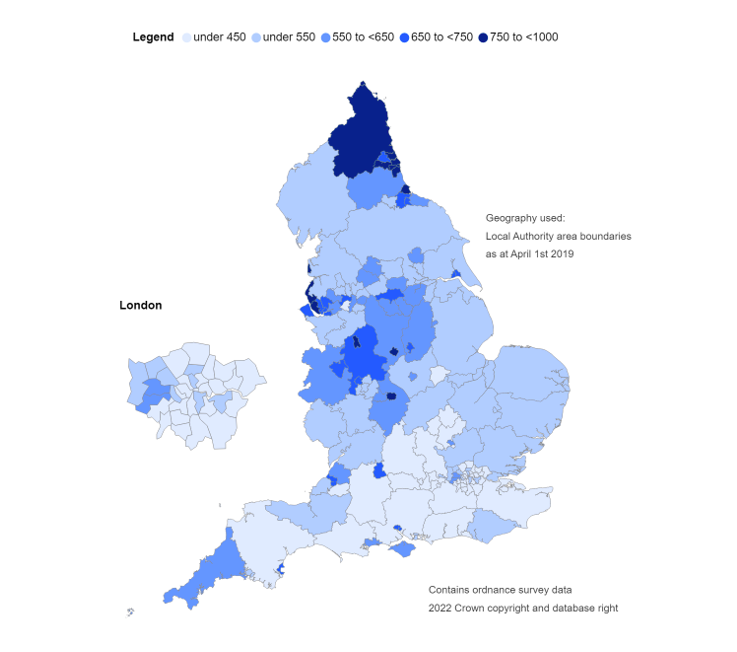

Liverpool no longer wears that unwanted crown but out of all the local authorities in England, we still rank eighth for alcohol-related hospital admissions per 100,000 (with 2,260), one space behind Knowsley (2,270). Notably, Liverpool, Knowsley, Wirral and St Helens all make the top 25. Considering there are 333 local authorities in total, that makes pretty grim reading, although — to reach for a silver lining — back when the Daily Post slapped its tag on the city Liverpool was firmly in first place with 2,582. Very small mercies though, especially when you tie in the fact that in 2018 it was estimated Liverpool loses £90 million a year in productivity due to alcohol and that it costs the NHS £46 million a year.

More recent statistics published by Rehabs UK have the city ranking third in the UK for alcohol dependency, behind Blackpool and Southampton. It’s no great coincidence of course, that of the top five (Blackpool, Southampton, Liverpool, Middlesbrough, Sunderland), four of these — taking in the Liverpool city region — contain some of the most deprived boroughs in the country.

Leaving Concert Square, I head along to Fitzgerald’s on Slater Street, where people gather outside around a man who clutches to a wheelie bin to prevent himself hitting the deck. Men howl with laughter and a couple of girls say that he should be helped, albeit unconvincingly. Inside, it’s too busy for conversation or indeed much else, so I stand like a sardine and order a Guinness. A sardine drinking Guinness.

In August 1866, The Times delivered a less-than-glowing appraisal of the city’s relationship with drink. “Liverpool has been pronounced the most drunken, the most criminal, the most pauper-oppressed, and the most death-stricken town in England,” it wrote. Which may be a tad harsh, but then the 19th century — as the local population rose and rose from 77,000 to 700,000 — was exactly when Liverpool became a drinking city.

Thanks largely to the booming port and ship workers that it attracted, a proliferation of pubs and bottle shops clustered in the areas the new population was living. Many politicians who didn’t share the newcomers’ image of Liverpool as a boozy free-for-all became part of the temperance movement, who believed the city’s ills were found at the bottom of the bottle. There were — in fairness — estimates of one pub for every 13 people in some areas.

But that’s history. And as temperance might be a hard sell in 2023, we now have the late night levy instead. It has taxed local bars for alcohol sold between midnight and 6am since 2017 with the proceeds used for fighting the alcohol-induced issues that occur at night. Unfortunately, a recent council-commissioned report cast aspersions on how effective the levy has been in reducing crime, calling out a “lack of transparency” from the council about how the money was being spent.

On the drugs side of things, the obvious and primary reason is also the ports. The rate at which local residents are taken to hospital with drug-related mental health problems is consistently among the worst in the country. Little wonder, when three years ago the National Crime Agency said that Liverpool “dominates” the drugs trade outside London. Indeed, the OHID (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, a government public health unit) have been testing cocaine levels in wastewater around Liverpool of late and, surprise surprise, it’s on the up. On my own night of journalistic bar hopping I only get the suggestive signal once (a “you look tired mate” in the toilets rather than a theatrical finger tapping on a nostril).

In 2007, Professor Ian Gilmore — director of the Liverpool Centre for Alcohol Research — told the Guardian: “It is impossible to have a celebration without alcohol and the amount of office parties and single-sex groups you see every night of the week drinking too much out in the restaurants in Liverpool is unbelievable. It has never been so cheap.” This — to me — feels like the one clear noticeable difference between Liverpool and say, Manchester. It’s a cheap place to get drunk if you want it to be. Whereas Manchester is now almost entirely under the stranglehold of the boujee bar, Liverpool clings onto the likes of Great Charlotte Street, a mecca of mid-afternoon karaoke dens with pints that hover in the £2-3 range, which is a vanishingly rare price for other cities.

Later in the night, sitting in the Blob Shop (on Great Charlotte) with a watery £2.60 lager, I speak to a woman called Sarah and her friend. Sarah practically screams as she asks where I’m from, originally. I say “Kent”, to which she replies a shrill “oooh posh” and lifts her shoulders back to signify poshness. I say it’s not that posh and that many places in Kent are really pretty awful. But this, of course, is exactly what a “posh Kent boy” would say and my denials only seem to fuel the fire.

Thankfully, the conversation turns to funny stories of drunkenness, a fertile field. I recall the time I watched a man throw up into a stein in Bierkeller. She recalls the time she drank too much on a date and threw up on his shoes. I recall the story from the top of the article about the Great Chair Chase of Bold Street. It gets a big laugh. She jousts back with a story so foul it doesn’t bear repeating. Time to call it quits.

A few days later and with a head that no longer throbs, I find myself in The Vibe on Paradise Street, which sells things like earth bowls and sea moss. I’m here to meet Jordan, a recovering alcoholic and drug user whose issues were tied very closely to a culture of binge drinking.

I suck through a straw into some green concoction, the ingredients of which I can’t quite recall. Probably kale. He doesn’t want his name mentioned — he isn’t too long enough sober yet (212 days) — so we set about coming up with an alias. He pushes for Sadio Mane (whose departure from Liverpool last summer was a “great source of tragedy in his life”), but I say that if I write “Sadio Mane (not his real name)” that might sound a bit odd, so we settle on Jordan, after Henderson.

He started drinking when he was 14 or 15, growing up in Stoke, but not “that heavily”. He went to uni at John Moores and thinks it started to become “full on” in those days as a carefree fresher. “You don’t realise it’s a bad thing at the time. But you’re just pouring back silly amounts every night, along with all the coke and the pills. But everyone’s doing it so it seems fine. Although I was probably doing it the most.”

And if he was “probably” doing it the most back then, when he left uni and got a job in the city it became quite apparent, going out most nights after work. The eventual consequences were the usual ones: damaged relationships, mates who “start to think you’re a bit of a dickhead”, incidents — like the time he turned up at 4am (“so pissed I had no clue what time it was”) at a girlfriend’s house banging on the door until her mum emerged in a dressing gown looking seriously wound up — that are hard to erase from memory.

In the end it was “night after night” of drinking plus coke when it could be afforded, which was quite a lot. When the coke came out, that’s when things went up a few levels. “I did loads of things that I don’t know how I didn’t get knicked for,” he goes on. “Daft things, fucking people over, being a massive pain to be around.”

The low point, he says, but also the turning point, was when he was back staying with his parents in Stoke temporarily and they asked him to leave because they didn’t want his obvious alcohol and drug use around his younger brother. He reached out to a friend of a friend, who invited him along to an “AA-type recovery group” and he just stuck with it. “I can honestly say that making that step, confronting what was going on, is the best decison I’ve ever made,” he says.

The question that I’m keen to understand is to what extent does a “binge culture” (to borrow that unpleasant phrase) feed into an “addiction culture”? Predominantly we probably think of addiction as being rooted in a deeper psychological distress or trauma, perhaps issues with their roots in childhood. Jordan, on the other hand, believes that while there were “certainly elements of that” he also thinks he just “went off the deep end and started drowning”.

“Really, it’s a mix of both” says Jacob Jones, who works at Change Grow Live (CGL), a national substance misuse charity with a base on the Wirral, talking about the referrals they get. I’m talking to him and Gerry Pangalis, who is the deputy service manager at the charity. Back in the summer of 2020 CGL moved premises, largely for the reason that — ironically enough — the old one was surrounded by pubs. The new building, essentially accidentally, happened to be surrounded by a number of other groups dealing with similar things; recovery services, a pharmacy, a GP, community organisations for people in recovery or with mental health issues. “Hang about, this almost feels like a recovery village,” Gerry recalls thinking.

And so, they made it into one, a “recovery village” as they now call it. It made sense, they all talked the same language, often dealing with people going through similar things, very often literally the same people. A dozen or so organisations, spread out across just a few streets, now work together sharing each other’s expertise and meeting to discuss strategy. The result, as the BBC reported last year, is that “Birkenhead is fast becoming regarded as one of the best places in England for addiction support”. Gerry sums it up succinctly: “It’s the concept of knocking on somebody else’s door and it never being the wrong door.”

Still, I’m fixating on the one question. “It’s difficult to quantify,” Gerry says of the exact role binge drinking or party culture plays in triggering addiction. The sort of data they collect wouldn’t spell out an exact answer. He does make an interesting observation however. He says he’s seen a “very steady increase” in recent years in people with dual addictions, such as cocaine and alcohol or alcohol and cannabis. These dual categories tend to skew much younger than single addictions and suggest behaviours around going out, or partying.

Change Grow Live now has one staff member stationed at Arrowe Park Hospital in Birkenhead every day of the week, speaking to people who have been admitted for alcohol-related incidents on the wards, getting referrals straight from the bedside so they can seek support the moment they’re discharged. It’s a “foot in the door” that took a while to establish, but it’s been an extremely important addition to their services.

They’ve also hired an alcohol intervention worker, who works with people who don’t need structured treatment like a detox or rehab but who are at risk of doing “serious damage to themselves” if they continue on the same path. Jacob says this isn’t for serious alcoholics, rather for “people going out and taking it a bit too hard on the weekend, every weekend, we’re putting these things in place to help prevent these things as well”.

This kind of behaviour, nipping it in the bud so to speak, is quite a rare thing in the world of recovery. As a general rule, most people wouldn’t seek out help until the issue is pronounced and close to unavoidable. Jacob does recall an “older gentleman” who used to do his drinking in the form of pints in the pub in front of a football match (the standard) until lockdown struck and he found himself sat about the house all day doing his drinking a lot by himself (less standard). He and his wife had a chat and decided they should seek support before things worsened. But this is something few people do.

Jordan is in a better place now, having repaired most of his relationships, regularly attending his AA meetings and working full-time in a tattoo parlour. “That whole world I fell into here, it did so much damage. I’m so glad to be out,” he says. Ultimately, as Gerry notes, “all major cities could be seen in the same kind of light, I’m not sure there’s anything happening in Liverpool city centre that isn’t happening in Manchester or Leeds”. If Liverpool does have a so-called “binge culture” then so do a hell of a lot of other places. And that’s probably the problem.

Comments

Latest

Searching for enlightenment in Skelmersdale

I’m calling a truce. It’s time to stop the flouncing

The carnival queens of Toxteth

The watcher of Hilbre Island

150 years ago, The Times said Liverpool was the most drunken town in England. How are we doing now?

Beer and loathing in Concert Square